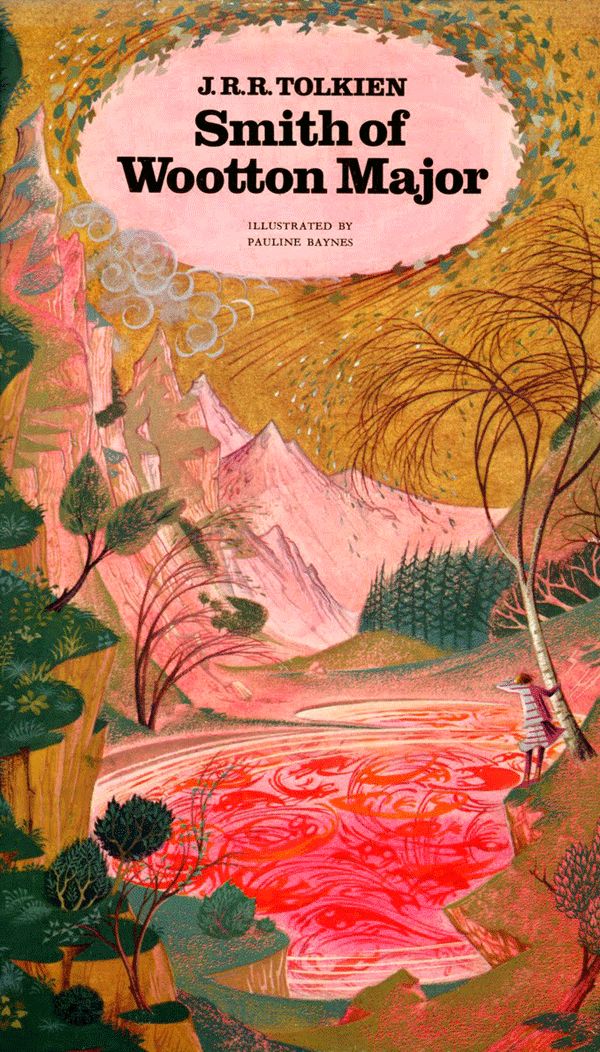

For the last post in this year’s September Series, it only seems natural to discuss the last work Tolkien published in his life, and the last of the tenuously-connected ‘Lesser Tales’ – Smith of Wootton Major. And discuss it we will – in a manner of speaking. Because this choice of mine to write about Smith is, alas, also a critical error of judgement on my part.

Smith might be my favourite thing Tolkien ever wrote. Ever. There’s nothing like the richness of The Lord of the Rings, and On Fairy Stories might have had a more profound influence on my thought. But for sheer enjoyment, I’ve never found anything to compare to Smith. I still remember the first time I read it – I was in my mid teens, digging through my mother’s bookshelves for something to occupy me, and stumbled across this slender and shabby Tolkien novella. I’d read LOTR by this time, at least three times, and the Silmarillion, and Letters and Unfinished Tales.

I knew Tolkien, I knew I was a fan of Tolkien. But I can’t say I would have read Smith if I weren’t, as there wasn’t much to recommend the book to me beyond the author. It was a dingy, old copy, falling apart a little, faded, bereft of any blurb to sell it. Nonetheless, I dutifully ploughed in, and quickly realised it was a light and silly little story, about cakes and children. Then, of course, I had the further realisation that my first realisation was horribly mistaken, and that there was something terribly compelling about this strange little story.

I actually don’t remember much else about that first read, except that the book shook me. I think I reread it a few days later, hoping to understand it a bit better, and once more it defeated me. That isn’t to say that I failed to read it, either – I finished handily within an hour or so. But I was just as disturbed by it and just as baffled by it after my second reading, too. And my third, and every other reading thereafter.

To this day, I don’t really understand Smith. I’ve read analyses by other people, and have often been fairly unimpressed by them – especially any and every reading that attempts to assign allegorical interpretations to the story. Verlyn Flieger, I think, stands rather apart from many others in fiercely resisting any interpretation of Smith beyond what it is, a story of Faery.

But I digress. The point is, I have nothing to say about Smith. No thematic connections to elucidate, no hidden details to reveal, no analyses to lay bare some secret at the heart of the story. I love Smith, and I have absolutely nothing to say about it, and never have. The one time I’ve previously written about it, it wasn’t really about Smith at all. And, given that I’ve got an entire blog post dedicated to Smith before me, that might seem to be a bit of a problem.

All of this is not to say that there is nothing to study in Smith, of course, my point is rather that I am not the right person to analyse it. It is, to my eye, a bafflingly simple work, a masterpiece of profundity. It’s sad, and funny, and intriguing, and beautiful, and perfect, and there’s nothing to say about it, no tenuous connection to be drawn or interesting tidbit to expound upon.

So in this post, I’m going to do something a bit different – I have nothing to analyse in Smith. Instead, I just wanna talk about Smith – Tolkien’s walker-hero, a wanderer in distant lands and a wonderer upon his wanders.

There’s a beauty in the nearness of those words, ‘wonder’ and ‘wander’. Both are Germanic in origin, and migrated into Old English, but even their Proto-Germanic roots have disparate origins (disclaimer: I am not a philologist). Yet, despite their lack of a common etymology, not only do they sound similar, they seem to conjure some commonality, to be complementary to one another; as is evoked in the 20th-century folk hymn I Wonder as I Wander.

Tolkien’s works are celebrated for several qualities, but I daresay that that dual sense of wondering and wandering are foremost among them. Tolkien’s stories are almost always concerned with a journey (literal as well as figurative), and with a sense of discovery, of peeling back the boundaries and experiencing the miracles at the edge of sight. And while I daresay there are plenty of examples where these twin sensations are explored (The Road Goes Ever On would seem a prime candidate), Smith is really the work where Tolkien just, well, writes about them. Smith is, at its heart, basically just the story of an ordinary man who goes on really long walks and sees extraordinary things – and that, more than anything else, I find highly relatable.

I’m not much of an athlete, but one of my preferred physical activities is going for a run, which inevitably leads to the amateur runner’s favourite question – “what’s your route, then?” And I never have an answer to that, because not only do I not have a route, I fiercely resist sticking to one. It’s probably bad athletic practice, but to me, one of the primary joys of running is the exploration of it, is finding some new path or turn or vista. I love discovering something unseen, going somewhere that I’ve never been before, and there’s no work of literature that captures that excitement better than Smith does.

Obviously, my runs are generally in my neighbourhood (though it is well worth saying that, having lived in my current city for just over nine years now, I’m still discovering new paths, even in the heart of the city), but when I go travelling, I also love to just go for a wander and see what I can find. There’s nothing quite like the sensation of coming across some yawning archway and passing through it, or spotting a glimpse of a tower and trying to get a better sight of it. There’s something intangible and thrilling about that sense of discovery, about finding something and knowing that you’ve never been there before.

I remember being in a city in Germany once, a relatively attractive and historic city, and having a grand old time wandering about and seeing the sights. But the most exciting and striking part was when I got lost, really lost, and somehow ended up wandering through a desolate construction site. It was (as far as I could tell) accessible to the public – I’m not a trespasser! – but it was most assuredly a place that I wasn’t ‘meant’ to be, which only added to the excitement of it. There was a gothic church, mournfully pressed up to the side of the dusty unbuilt crater, which seemed important to me.

Were there more beautiful, more significant, more interesting places in that city that I might have seen instead? Most definitely. Would I have rather gone to them? I’m not so sure. That sense of loneliness, of urban desolation and unfulfilled potential, was haunting and palpable, and there was also a taste of risk, of not quite knowing where I was. Plus, like I said, there was that sense of having discovered something – I could have followed any number of tourist trails and seen ‘better’ things, but I would never have ‘found’ a single thing. That desolate and barren waste was not beautiful, was perhaps not even special. But it was special because I wandered there for a while, because I had not been there before and may never chance upon it again.

Smith’s journeys in Faery may be more fantastical than anything most can manage, yet there’s a remarkable groundedness to his wanderings. It may be unlikely for you or I to stumble across elven mariners or lakes of glass, but the act of wandering is nonetheless conducive towards the sighting of such marvels. Smith’s experiences of Faery are not unrealistic – if anything, they are extrareal, extraordinary.

It is also striking, I think, that Smith’s experience of these wonders is explicitly gained through his travelling to them. There is a dreamlike, surreal quality to many of Smith’s experiences, but never a hint that he has actually ‘dreamed’ them. Smith’s journeys are deliberate and conscious affairs, though he may not know to what end or experience he is travelling, and that connecting of journey and fantasy is (I think) not only deliberate on Tolkien’s part, it’s highly important. Tolkien writes slightingly of fairy-stories that employ Dream to explain their fantasy in On Fairy Stories, and Smith would seem to be Tolkien’s thesis in support of this argument – to Tolkien, Faery cannot be reached without a journey to get there and, conversely, any journey (however minor) may wind through the marches of Faery.

But if a waking writer tells you that his tale is only a thing imagined in his sleep, he cheats deliberately the primal desire at the heart of Faerie: the realisation, independent of the conceiving mind, of imagined wonder.

‘On Fairy Stories’, JRR Tolkien

That ‘imagined wonder, independent of the conceiving mind’ is as good a description as I can imagine for the twinning of wandering and wondering. Because, ultimately, the joys that one gains through such explorations are indeed imagined, there is nothing that can inspire one save one’s own curiosity. Yet the joys are sparked and fed by external stimuli, however great or small, and the more one engages with those joys, the more readily they come.

Often, when I’m out in town, I find myself overwhelmed by how big things are. It’s easy not to appreciate, of course, but even little things are really quite big. Bus shelters, lamp posts, traffic lights. These are big things, mysterious things, things that, frankly, a person cannot make or move. And yet here they are, made by human craft and transported all across our cities, where they linger evermore. For some reason, bus shelters in particular elicit this sense in me, I don’t know why.

Then you have little laneways, hidden pathways, winding stairs that lead into some shadowed corner. It is easy enough to glance down a narrow lane and dismiss it as not going anywhere, and often it does not go ‘anywhere’. Yet it always leads somewhere, and the finding of that where is reward enough for me. There is nothing quite like the excitement of taking a first step down a path that you have no ‘business’ being on (by which I mean, of course, that there is no reason for walking on the path other than that you are there, and the path is too).

Most exciting of all, though, is a sudden glimpse of some hitherto unseen stretch of land, some new perspective or sight. Sometimes, this will simply be a novel view of things previously seen, an unexpected and welcome panorama of places already explored, now laid out in their place, allowing you to understand the layout of the labyrinth through which you’ve stumbled with eyes wide open. Best of all, though, is the cresting of a hill or the climbing of a tower that has stood guard between one land and the next, and the sighting of a whole new region to explore, rolling out before you like some alien world.

The primary enemy of such explorations is, alas, a map. A map is a reminder that someone has been here before, has marked out the territory in exact and careful detail. A map is also a temptation, temptation to follow some ‘optimal’ route rather than to come to a crossroads, and turn down the path most attractive to you at that moment. This is not to say that becoming “truly” lost is ideal, of course – a journey is not much fun if safety cannot be found at the end of it! Rather, if a map (or more realistically, a phone) accompanies such wanderings, it should be a guide simply to extricate oneself from any particular problems, rather than a constant crutch. And though I’ve certainly turned to my phone on many an occasion when the day is drawing to a close and I need to return home, there is also an especial relief to be felt when, independent of any external aid, you chance across some landmark or some sight of the path back, and thus find for yourself the way back to safety.

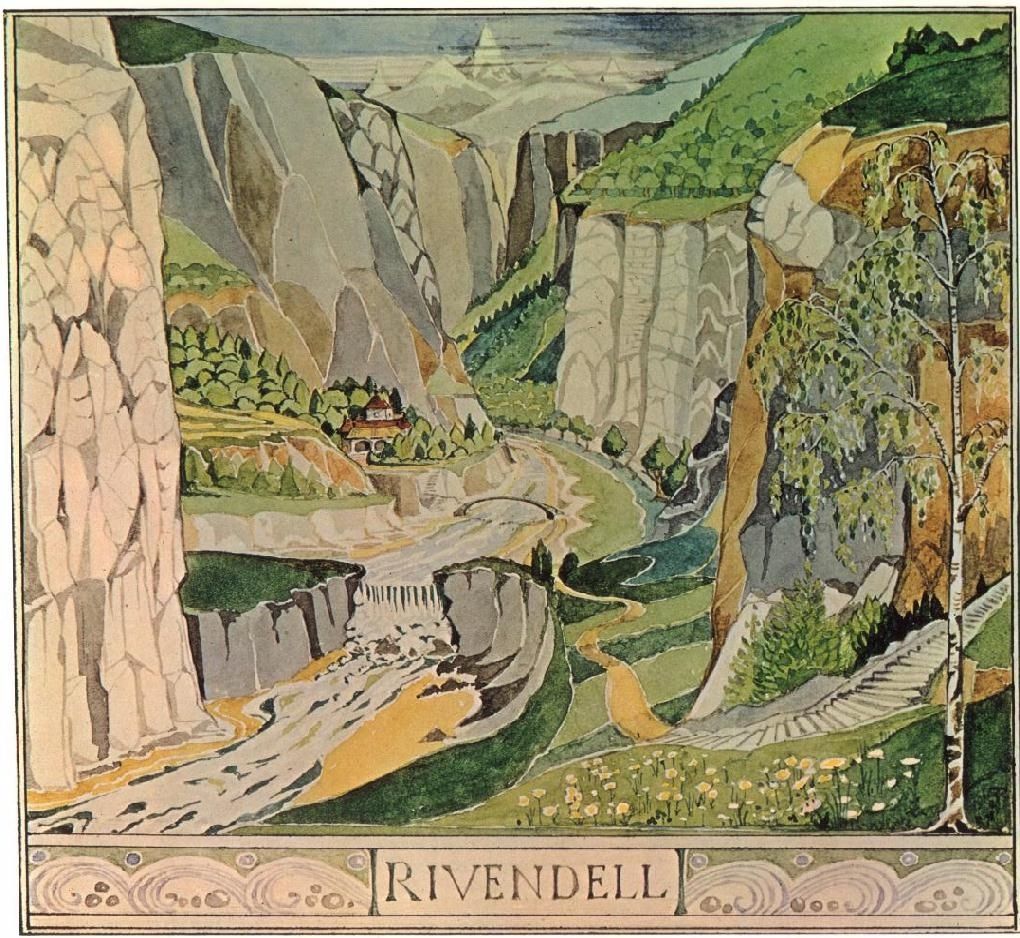

Tolkien was known to be fond of rambles, and (to the frustration of some of his frequent companions) never seemed especially concerned with ‘getting somewhere’, rather enjoying the route than striving for some destination. Indeed, Farmer Giles was reportedly conceived when the family Tolkien were on an excursion through the Oxford countryside and became caught in a storm; and Rivendell and the Misty Mountains (at least) owe some inspiration to Tolkien’s 1911 trek through the Swiss Alps and the Lauterbrunnen region.

It is not hard to catch a glimpse of Faery in Lauterbrunnen, but one must not travel so far to discover Faery, either. Smith delights in the smallest glimpses of Faery as well as the great and (crucially), Smith does not argue that Faery is so terribly distant, either. Though Smith sometimes goes on great journeys, and sometimes on lesser, it never seems as if it takes him long to get to Faery, as it were. Faery never seems to be all that far from Wootton Major, even though few are blessed with the finding of it.

I think that’s crucial, too. The joy of exploring need not be withheld for exotic and far-flung locales (though being somewhere alien is a sure way to whet the appetite), all it needs is to step out the door and be swept up by the Road.

Ultimately, I love pretty much everything in Smith – the sense of melancholy, the portrayal of Elves, the relationship between Smith and Nell and Ned, the secondary story of Nokes and Alf – but primarily, I love it for its portrayal of wandering, and wondering. The oft-quoted phrase that ‘It is about the journey, not the destination’ is, I suspect, not intended to be read literally, which is a great pity. Because it really can be about the journey, and I don’t know that I’ve ever found a work of fiction (or fact) that celebrates the joy of the journey more effectively than Smith of Wootton Major. That, quite simply, is why I love it – because it captures the same giddy joy that I feel when I go wandering.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading – feel free to check out anything else you may be interested in on the blog, there’s plenty more to discover! Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter to stay up to date with The Blog of Mazarbul, and if you want to join in the discussion, write a comment below or send an email. Finally, if you really enjoyed the post above, you can support the blog via Paypal. Thanks for reading, and may your beards never grow thin!

Loved this post.

Are you going to discuss ‘Roverandom’ in any future posts? That is absolutely about journey !

Thanks! And no, no plans to cover Roverandom any time soon, but if I come up with something worth writing about in it, then I’ll absolutely do so!